About the Summer School

As a continuation of the summer school on the environment that has been held successfully for several years at the Department of History, UGM, this year’s summer school raises the theme of human ecology in facing the challenges of creating new environmental governance for the 21st century. Referring back to the capitalocene critique of the problems of environmental governance shaped by capitalism in the 20th and 21st centuries, this summer school aims to explore the ontological forms of environmental governance outside of capitalist extractivism and state modernization. Here, we will explore and recall stories and knowledge that have long been held in the collective cultural memory of Indonesians – and imagine forms of ecological nationhood and citizenship rooted in local traditions and understandings.

This year’s curriculum uses a human ecological perspective that has been developed by the father of Indonesian ecology, Otto Soemarwoto, who places Indonesian humans as part of the Indonesian ecological network. In contrast to the Western ecological conservation view that imagines forests, oceans and the ‘original’ environment without humans, Otto imagines that humans themselves are one of the main species that have placed themselves in the ecological network of nature. Solving climate governance issues in this century must be based on an understanding of the centrality of humans in these ecological networks. Without it, ecological views and environmental movements will have an anti-human tendency. Without envisioning a shared ownership of the human ecology, the concerns of the people, especially in the South, will threaten the failure of this process of civilizational change. The view of removing humans from nature developed during European imperialism and is closely related to the Western racist idea that the main ecological problem of nature is the existence of indigenous people in it.

Human ecology envisages that human civilization from its inception cannot be divorced from the close relationship that humans have with the biological germplasm and geological materials and energy flows that underpin the entirety of the natural world. Humans must learn to create a harmonious and mutually beneficial relationship with this network; humans learn to respect the animals, plants and landscapes of his homeland, as well as the energy flows that come from within the earth, from the sky and from the sun and water that flow in various forms: rain, rivers, groundwater and others. Humans build these ecological networks that they bring with them when they move; when our Austronesian ancestors migrated from Taiwan, we brought with us a series of animal and plant allies that transformed the nature of the destination. From rice, tubers, buffaloes, dogs, pigs and so on, our ancestors did not only consist of humans, but a network of humans with their natural creatures. Colonialism is often thought of as ecological colonization and, in Western expansion, uses bioterror – such as viruses and bacteria – on other human ecologies. Transmigration program, for example, also rely on ecological attacks. Indigenous colonization takes the form of uprooting and destroying the human ecological networks that have sustained them over the years; for example, the slaughter of hundreds of millions of bison herds on the continental prairies of the United States aimed to destroy the ecological basis for Native American culture.

The source of human ecology is in society. But it is often hidden due to the uprooting and disconnection of this cultural ecology as a result of extractivist capitalist expansion and state modernization. This traumatizing process defines human ecology as a disease, something problematic and something to be suppressed. People who are caretakers of human ecological knowledge are seen as conservatives with traditional knowledge that is unscientific and nonsense. Capitalism and modernity imagine that nature can be integrated into the process and flow of human civilization – and so humans are uprooted from their ecology. Kohei Saito reminds us that this disconnection was already recognized by 19th-century thinkers and that the revolution out of capitalism must be based on a consciousness to reincorporate the environment in the flow of our civilization.

There are three approaches that will be used in this summer school:

- Site-centered learning approach

- Historical documents/oral sources approach

- Multidisciplinary approach

For those who interested in this summer school, please register to this link below.

Lecturers

- Prof. Gerry van Klinken (University of Queensland/KITLV)

- Prof. Diana Suhardiman (KITLV)

- Prof. Dr. Nawiyanto (Department of History, Universitas Jember)

- Dr. Agung Wardana (Department of Environmental Law, Universitas Gadjah Mada)

- Dr. Guanmian Xu (Department of History, Peking University)

- Dr. Harro Maat (Wageningen University)

- Dr. Farabi Fakih (Department of History, Universitas Gadjah Mada)

- Siti Nurleily Marliana, M.Sc., Ph.D. (Department of Biology, Universitas Gadjah Mada)

Some reminders

- The program will be conducted in English and Bahasa Indonesia;

- Only around 30 students will be selected for this summer school;

- The fee for this program (Rp. 500.000) is payable upon acceptance announcement;

- The organizer will contact the accepted participants through the email address provided;

- The organizer will not provide accommodation (lodging) and transportation for participants.

This summer school is organized by The Department of History Faculty of Cultural Sciences Universitas Gadjah Mada in collaboration with KITLV Leiden and WALHI.

Last update: June 2, 2024

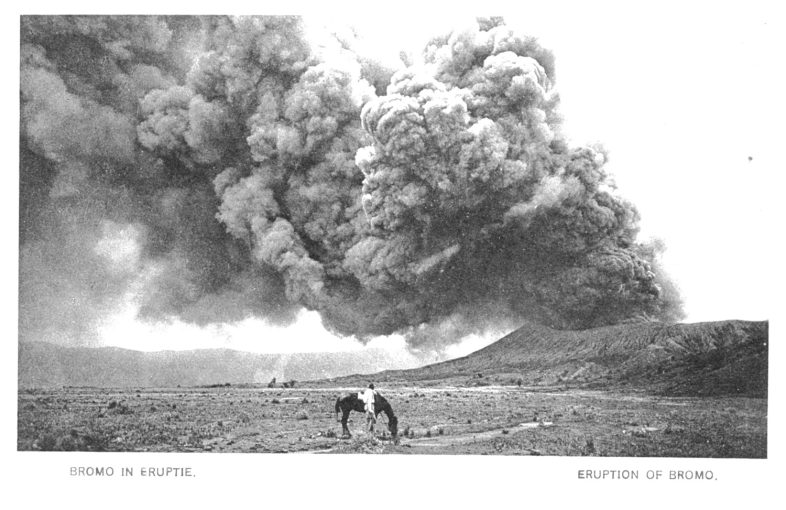

Image: Eruption of Bromo [Circa 1910] (http://hdl.handle.net/1887.1/item:843182)