Peter Boomgaard became important in the development of Indonesian historiography. For some historians his expertise in pioneering environmental history is a challenge. He provides an alternative to mainstream historiography – which used to be militaristic and political. Why is this environmental historiography unique? Boomgaard’s idea no longer places human relations between humans – which is a feature of political, military, or even social historiography in subsequent social developments. History is not about war and power. Peter Boomgaard does not eliminate the role of humans, because humans are an important element of history. However, – through the idea of environmental history – he has the idea that history is also the relationship between humans and nature. So history has wider interdisciplinary possibilities, even including the realm of science which is no longer fixated on the social science approach. So history can discuss the relationship between humans and nature: interactions with fauna, natural disasters, and the history of disease outbreaks.

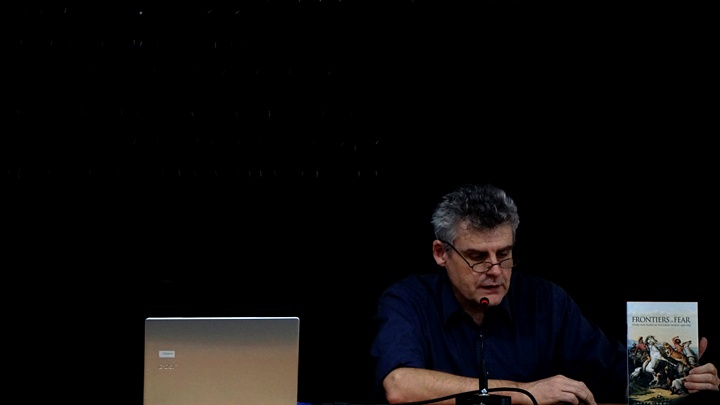

Peter Boomgaard’s expertise not only deserves to be remembered, but deserves to be highly appreciated. The appreciation is in the form of a review of his ideas. Departing from this, the Department of History FIB UGM held the event “In Memoriam Peter Boomgaard” with the theme “Humans, Environment, and Tigers: The Influence of Peter Boomgaard’s Heritage in History and Social Studies”. The event was held on Thursday (6/2) in the Multimedia Room, Margono Building, lt. 2, FIB UGM. Several presenters filled the event, including: David Henley from Leiden University, Marrik Bellen from KITLV, Didik Raharyono an expert on tiger studies, and Sri Margana from the History Department, Faculty of Economics, UGM. The presentation starts at 09.30-16.30 WIB.

Peter Boomgaard’s Track Record

During his lifetime Peter Boomgaard (1946-2017) was Professor Emeritus of Environmental History and Economic History of Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia, at the University of Amsterdam. In addition he is a senior researcher at KITLV. In recent decades he has been interested in the study of the history of forestry and the environment. In addition he took an interest in the concentration of medical history. For the latter, he conducted a series of research on the history of leprosy in Indonesia and Suriname in 1800-1950. On the other hand he is the coordinator for EDEN (a research program of KITLV). The program is intended for all research related to environmental history in Indonesia in 1600-2000.

Peter Boomgaard’s career did not end at that point. His thinking is very influential. Especially in several educational institutions that he had held. He has held important positions at Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Vrij University Amsterdam, and the Royal Institute Of Tropic (KIT). It’s not enough, Peter Boomgaard has served as Director of KITLV from 1991-2000. In addition to teaching, he is listed as a member of the Association of institutions that study Southeast Asia (EURO SEA), and was secretary in 1992-2004. Apart from that, in the period 1982-1996 he was the editor and editorial board of various international scientific journals.

Almost half of his life, he – consequently- dedicates himself (which is his interest) to environmental history research, especially in Indonesia between 1500-1950. In the field of environmental history, Boomgaard has written the history of forestry, plants, wildlife and pets. In 2007, he published a textbook on the environmental history of Southeast Asia. For his dedication to environmental history, he has been awarded many awards. One of them is from Rachel Carson (an association of people who care about the environment) in Munich, Germany for her work that describes Humans, Animals, and the Environment. Then he also received appreciation from NWO (Dutch Organization for Scientific Research) for his work on the History of Leprosy in Indonesia and Suriname, 1800-1950.

Tiger(?)

Several presenters at that time, many took the tiger as a research topic. Approximately four presenters. In Peter Boomgaard’s notes tigers are not a new topic. Peter Boomgaard’s Frontiers of Fear alludes to tiger pests. In Priangan in 1855, 147 people died from a tiger plague. The topic of the tiger is apparently quite in demand. Didik Rahardjo, who researched the Javan tiger, explained his research. An interesting fact is that he did not get the Javan tiger he was looking for. However, he found parts of the tiger’s body. Sometimes nails, and skin. The Javan tiger has been hunted

Even so, tiger hunting has been going on for a long time. Since colonial times, hunting for striped animals has become a hobby. In the Surakarta Kasunanan Palace and Yogyakarta Sultanate, even tigers have become a spectacle. They made a big circle then they stabbed the tiger to death. It is called “rampogan matjan”. Apart from spearing tigers, in Vorstenlanden there are also often pitting against bulls – his name is Rampogan Mahesa. There are several opinions about the tiger rampogan. The incident of the stabbing of a tiger in the realm of the Palace, some opinions state that it is a sin-removing ceremony. On the other hand, there is also a fight between a bull and a tiger which is interpreted as a fight between the natives and the Europeans. The bull – which is slow but has extraordinary stamina – represents the natives. Meanwhile, the Tiger – who gets tired quickly – represents the image of Europeans.

The tiger in some ways represents something (idea) that is important. The relationship between tigers and humans is also a reflection of how humans view nature. We can see a shift in human perspective. The Tiger used to be a cult thing. The Javanese, at one time, referred to the Tiger as Mbah or Si Mbau Mutual. Along with that, there are those who consider tigers as human brothers, by using them for certain purposes. Maybe it’s the same as when humans look at nature that brings benefits to themselves – for example a horse to ride. Gradually, people’s views shifted that nature – including tigers – had commercial value. It can also be exploited.

History is basically about humans. But Peter Boomgaard provides an alternative, to present a more proportionate history. That nature is also a part of our daily life. Human treatment of nature – fauna, plants, and in certain cases giving birth to natural disasters – deserves to be written down and included in historiography. Ultimately, remembering Peter Boomgaard is celebrating the spirit of Peter Boomgaard’s environmental historiography. (Sej/Bagus)