The Department of History held a socialization and sharing experiences about Merdeka Belajar Kampus Merdeka (MBKM) program which was held online via zoom with undergraduate students. This event was held on Wednesday, 25th May 2022 at 10.00-12 WIB which was guided by Satrio Dicahyo, M.A.. This event also invited some speakers, Dr. Mutiah Amini as the Head of History Undergraduate program, Zahra Aulia as a participant of IISMA program, Lesta Alfatiana as an Alumnus of Kampus Merdeka Bank Indonesia, and M. Rozzaq as an alumnus of collaborative study program with ISI Yogyakarta.

Department of History UGM held a series of online discussions and book reviews with Rommel Curaming, Ph.D., from University of Brunei Darussalam. The series of online discussion and book review events will be held for two days, namely Wednesday and Thursday, December 8-9, 2021. Both series of events were held through the Zoom Meeting platform and broadcast live on the UGM History Department’s YouTube channel.

The online discussion is held from 16.00 to 17.30 WIB. The online discussion was opened by Satrio Dwicahyo as a representative from the UGM History Department and was later taken over by Yuanita Wahyu Pratiwi as moderator. After that, Rommel Curaming started the discussion by making a presentation. Budiawan, Ph.D, a senior lecturer in Cultural and Media Studies at the Graduate School of Gadjah Mada University, was also the discussant in this first series of discussions.

On Thursday (18/11), Department of History, UGM, held a book discussion with Dr. Arnout van der Meer, a historian from Colby College. In this occasion, Arnout explain his newest book entitled Performing Power: Cultural Hegemony, Identity, and Resistance in Colonial Indonesia. Guiding by Wildan Sena Utama, this discussion was responded by Sri Margana. This event also can be accessed by Departemen Sejarah UGM YouTube channel.

The book was published by Cornell University on 15 February 2021. This book explored how colonialism was legitimated and opposed by indigineus society daily life in the 19’s and early 20’s century. Arnout explained how resistance was identified on their language, manners, material symbol and status, even the motion and body posture. Through this book, Arnout aims to increase the understanding of the readers about the history of colonial Indonesia. For more information about this book, the online version can be accessed in this link. The audience hopes this book will be translated to the Indonesian version soon.

The History Department of FIB UGM held an online discussion or webinar on Friday, November 12, 2021 through Zoom Meeting. The webinar is entitled “Provenance Research Collaboration and Restitution of Colonial Objects”. The webinar, which will be held at 16.00-18.00 WIB or 10.00-12.00 AM CET, is specifically intended for UGM History Masters and Doctoral students. Dr. Sri Margana, UGM History lecturer, and Klaas Stutje, PhD, historian of PPROCE, the Netherlands, were the speakers and discussants in this webinar. In addition, this online discussion also brought Yulianti as the host.

Badan Keluarga Mahasiswa Sejarah (BKMS) has successfully held the 2021 History Week Opening Ceremony on Saturday, October 2, 2021. The opening ceremony was held online through the Zoom Meeting platform and live broadcast on the UGM BKMS YouTube channel. This year’s History Week carries the theme, “Medical Horizons in Historical Records: The Face of Reconstruction of Health Historiography in Indonesia” (Cakrawala Medis dalam Catatan Sejarah: Wajah Rekonstruksi Historiografi Kesehatan di Indonesia). The Opening Ceremony of History Week 2021 was hosted by Egit Andre Kelana and Faradeva Fathia Kurminta, UGM History Students.

Harvard University Asia Center organized a discussion series entitled Southeast Asia Lecture Series on Tuesday, September 28th, 2021, Farabi Fakih, one of the history lecturers at Gadjah Mada University, was the speaker of the discussion. The topic of the discussion was The Rise of Managerial State in Post-Independence Indonesia (1950-1965). The discussion started at 10.00 EST or 21.00 WIB on the Zoom platform and was attended by 56 participants. Farabi presented a summary of his book entitled Authoritarian Modernization in Indonesia’s Early Independence Period: The Foundation of the New Order State (1950-1965). More specifically, Fakih talked the authoritarian modernization under Soekarno’s rule.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been a great shock to humanity. In one night, the world that was busy welcoming the second decade of the 21st century must abruptly close. The economy suddenly plummeted together with the unexpected yet impactful disruption in socio-cultural activities. The government underwent every possible measurement to confine people at their houses or designated quarantine facilities while struggling to provide subsidies for impacted work fields. In confinement, people hardly adjust themselves to the situation while pondering whether humanity could survive this pandemic. Amidst the reflection, a question popped up: the Covid-19 is not the first pandemic in human history. To what extent have we learned from our past experiences dealing with similar issues?

__________

Course Title

Resilience and Control: Transmissible Disease and the Rise of Modern Society

__________

Course Description The Covid19 epidemic has reminded all of us of how fragile the relationship between man and nature has always been. Modern society to a significant extent was based on the mythology of the control of nature by man-made science and the reduction of risk of the dangers lurking outside of human civilization. The latest Anthropocene-approach to understanding human and the natural world tend to emphasize human effect on nature. Human civilization became the determiner of a fragile and weak natural system ravaged by the activities of global man. While the discussion on Risk Society also focused on the dangers of civilizations and the running way of technology to the detriment of human society and civilization. The fear always comes from the dangers lurking from within human civilization. This idea of the scientific conquest of the natural world was a central myth of modern society. Yet, just a century ago, the idea of the natural order controlling human fate and civilization had reigned supreme. Capitalism and industrialization had by then expanded to towering heights, producing hellish landscapes of the Satanic mills or the tragedy of the bondage laborers of tropical plantations. Yet these landscapes were rarely seen as taking over nature. The industrialization of the 19th century and the greater human civilization was still seen to be eking its existence on the margins of the natural world. Yet, it was also at this same period in which this gradually changed. In particular, the various technologies that appeared to eradicate transmissible disease and control the pathogenic dangers of nature were afoot. Hygiene and medical biology began to be developed based on the novel idea of the germ theory, the idea that much of the disease that has inflicted humankind was the result of tiny creatures invisible to the naked eye. This hygienic triumph changed so much of how we live, act and think that it is very much probable that the modern world that we know can only be understood to result from the absolute and unassailable control of modern hygiene and modern science. The Covid19 pandemic also alerted us of this towering control of science over the human freedom that we’ve conveniently forgotten. Like Plato’s cavemen, the ropes of scientific controls over our lives and civilizations were suddenly revealed as it was constructed in order to stave us off from the forgotten dangers of pathogens. Instead, we relive our premodern fears of nature and understood once again the fragility of human civilization and the hubris which has made us forgotten the bondage that it created. The exploration between modern society and transmissible disease in this years’ Summer School on Transnational History is not to reinvigorate the old trope of man versus nature, but in fact to understand the entanglements between the biological and the human world. The myth of modern society was exactly rooted, as noted above, in the illusion of carving the natural and the human world as separate spaces. Instead, we look at how transmissible diseases, like all global biological processes, has a way to make us rethink and understand the role of pre-modern human societies, the society before hygienic science and its management retooled society since the early 20th century. Alison Bashford has conducted studies on how various diseases determined different regimes of control based on the current notions of race, gender, and other identities. She saw how ideas of white male masculinities were tied to Australia’s effort to maintain a white society in the tropics. Warwick Anderson on the other hand saw how racial ideas of segregation and differences were applied to the colonial control by Americans in the Philippines. The disease was thus manifestations of behaviors and racial characteristics of the Filipinos. Covid19 alerts us of these synthetic and often nefarious regimes of controls which, on the surface, were thrust to society in the language of science and public policy, but which has always been rooted in the manifestation of the racial, gender, religious and other prejudices. These forms of control were also important in creating the new modern subjects – to be behaviorally controlled into one kind of modern man. He or she would eat in a certain way, move in a certain way and think in a certain way. Thus, the question of scientific conquest of nature seemed less about the natural world than it was about humans. It can also be seen as a scientific conquest of humans and humanity. Yet, there is also another facet to this story. The creation of technology and control of transmissible disease could also provide an empowering opportunity to various societies. The control of disease opened the chance to expand the population, local societies could reclaim and change the behavioral controls of science, and identities always thrived despite the various forms of spatial and behavioral control. Human ingenuity and resilience were not just a lucky component, it was an inherently important one for the success of modern society. It was exactly in human resilience, in its ability to adapt and strategize new ways of living with this control that allowed for the modern hygienic control to succeed. Human efforts to subvert regimes of control represented the continuation of human freedom and the human spirit in the advent of such transcendentally global mechanisms of control. The various technologies of control from public health and hygiene, town planning and architecture, transportation technologies and management of travel, engineering and food science, ideas of morality, identity and new subjectivities and others – reflecting on racial, gender, nationhood and others, represented both the dangers and promises of this new modern society. The similarities of these technologies and how they spread through transnational forms represented the ways in which modern society became increasingly entangled. The exploration of the rise of this society, the entanglement of the local and global within the context of both scientific regimes of control and its interconnection with imperialism, racism, and other non-scientific norms of order, the resilience of various societies in subverting these controls and the empowering effects of these transnational forces represented the core of a human-biological perspective in understanding the rise of the modern world. This is what will be explored in the Summer School of 2021. It is an homage to that scientific world of control that had seemingly died in 2020, but which will continue to live on. Disruption like the Covid19 allows us to rethink the relationship between behaviors, space, and identity in the modern world – who and why are some winners and others lookers in these new strategies of control. It also allows us to see histories in the region and the wider world as transnational and entangled exactly because of the interaction between local societies, global capitalism, and the wider natural world. It is important to understand that this world never ended, these interactions between the global, local, and natural remain the most important relationship of human society. In this regard, we will ponder upon how to deal with these divergent questions in a transnational and entangled way. We will ponder together and share ideas from our own localities in order to see this history as local, national, and transnational processes.

About the Scholarship

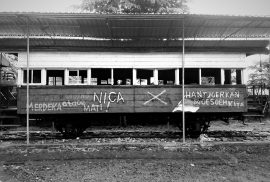

In order to encourage the continuation of the tradition of historical study about Independence Revolution, Department of History developed a special program in the form of research scholarships for master and doctoral students. This program is aimed to research, write scientific publication, or final assignments about the period of the Indonesian Revolution in the years 1945-1949. this research scholarship scheme is the part of cooperation collaborative research program between Department of History UGM and KITLV Leiden “Proklamasi Kemerdekaan, Revolusi, dan perang di Indonesia, 1945-1949”. this scholarship program will be held at odd semester of academic year 2020/2021 and 2021/2022/

Research Theme

The big theme of this research scholarship program is “Indonesia Revolution 1945-1949 in regional and global context”. the theme included, but not limited, to this aspects: social, culture, art, ethnicity, economy, religion, diplomation, politic, government, logistic, transportation, technology, military, gender, family, minority, education, etc.

Terms and Conditions